A new white paper from PwC, sponsored by AMAFORES, La Asociación Mexicana de Administradoras de Fondos para el Retiro (The Mexican Association of Retirement Fund Administrators) , looks at the best practices for the pension fund industry in the wake of the global financial crisis of less than a decade ago.

The paper offers three Big Points:

- Asset allocation strategies have become increasingly important since the crisis, so that one has to re-examine even such an old chestnut of an idea as diversification;

- The balance of in-house management on the one hand and outsourced management functions on the other is important to performance monitoring and cost control; and

- Watch those governance structures! They either “ensure sound processes and organization,” or they fail to do so.

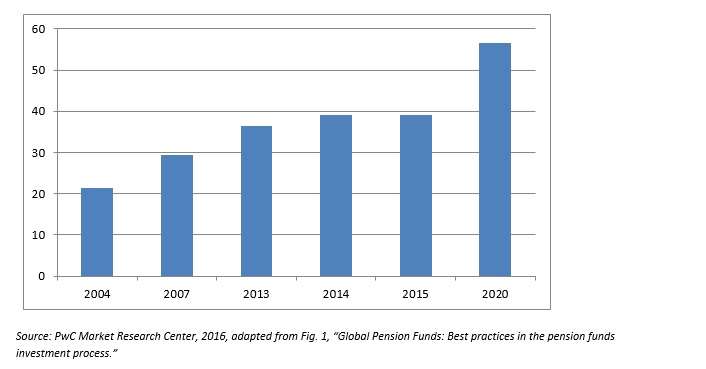

The graph below illustrates the strong asset growth of the global pension fund industry, as measured in trillions of US dollars, both recorded and projected.

Source: PwC Market Research Center, 2016, adapted from Fig. 1, “Global Pension Funds: Best practices in the pension funds investment process.”

Selling the Bonds, Then What?

As to asset allocation: global pension funds have long invested heavily in fixed income instruments. But this is changing. The state pension funds in the United States, for example, invested 90% of their assets in fixed income or held it as cash back in 1952. Forty years later that figure had dropped to 47%. Twenty years after that (so in 2012) it had dropped further, to 27%. An acceleration of this shift has been rendered necessary by decreases in the sovereign bond yields in the U.S., in the Eurozone, in the U.K., and in Japan since the crisis.

For example, in 1992, the 30 year Treasury rates wavered around 7.7%. CalPERS, which needed an 8.8% rate of return, could put a good deal of its assets into Treasuries, knowing it only had to beat those instruments overall by 1.1%. But by 2012, Treasury rates had dropped to 2.9%. Even though CalPERS lowered its return assumption to 7.5%, it still had to beat the Treasury rate by 4.6%.

The shift away from debt instruments has to a great extent been, as one might have expected, in favor of equity. But it has also, especially post-crisis, been a shift in favor of alternatives. PwC understands “alternatives” to include hedge funds, as well as infrastructure, real estate, and private equity funds. Understanding the word in this sense, one can say that state pension funds more than doubled their alternatives’ exposure between 2006 and 2012. Alternatives went from being 11% of those portfolios to 23%.

Alternative investments are of course more volatile than traditional investments. But they can lower a portfolio’s overall volatility by the magic of low correlation: by zigging when other assets zag.

Insourcing portfolio management

Let’s look to the second of the three Big Points mentioned above. A Canadian participant in a survey run in connection with this white paper spoke of his “desire to bring more decision making in house – mainly due to value for money and potential misalignment with overall strategy.”

PwC cautions, though, that in Canada or elsewhere the advantages of such a change should not lead to euphoria. All pension funds that make a decision to decrease the extent of their outsourcing “should be very clear about what they will gain and lose from doing so – insourcing in today’s dynamic investing environment requires highly specialized talent.”

A sound governance structure

The third of the Big Points covered in the white paper involves proper governance, which translates as “much stricter rules on transparency, structure, monitoring and supervision” than those that obtained for your fathers’ pension fund.

Many alternative investments have no daily pricing. “The common practice,” the white paper says, “is to have quarterly valuations on those asset classes.”

The white paper also gives some attention to the way the boards of funds on the one hand and the investment committees on the other hand share responsibility. It observes for example that in the Finnish pension fund Varma, the investment plan has to be confirmed by the board each year.

In general, governance structures have to be such as to “hinder conflicts of interest on the one hand” while easing “red tape associated with investing” on the other. Balance is the key.