Sarah Bernstein, of the Pension Consulting Alliance, has prepared a discussion paper for the benefit of the Vermont Pension Investment Committee, on climate risk divestment.

Specifically, Bernstein wrote in reply to a request from the VPIC to examine three divestment tracks of common intent but differing levels of generality: thermal coal; ExxonMobil; fossil fuels.

The gist of the paper is that divestment is not the best way to address climate risk issues. It would be better for VPIC to make use of its proxy votes and to engage with management of the companies involved.

Bernstein quotes a report from Sidley Austin LLP that contended that “in late December 2016, proxy access reached the tipping point ….Through the collective efforts of large institutional investors, including public and private pension funds … shareholders are increasingly gaining the power to nominate a portion of the board without undertaking the expense of a proxy solicitation. By obtaining proxy access (the ability to include shareholder nominees in the company’s own proxy materials), shareholders will have yet another tool to influence board directors.”

Indexes and Inclusions

Also, even looking strictly at the make-up of the portfolio, there are better strategies than divestment. VPIC should consider whether it is relying on the right indexes for the passive portion of its equity investments. There are “a multitude of market-wide benchmarks that seek to offer investors better overall risk-adjusted returns than market-cap weighted indexes.”

VPIC could put its concerns over climate change into action not by what it excludes from its portfolio, but by what it includes, by “shifting a portion of [its] assets to strategies that are expected to stimulate and benefit from long-term shifts to a low-carbon economy.”

For example, within the public equity domain, VPIC could invest in a fund benchmarked to MSCI’s Low Carbon Index which re-weighs securities to reduce the carbon footprint while continuing to track the underlying core benchmark.

The VPIC staff itself studied divestment in 2015. One of the differences between this study and that one is that Bernstein defines the fossil fuels industry somewhat more narrowly to include only companies that own fossil fuels reserves. The 2015 study had included the whole global industry classification standard for energy.

Further, the definition of “coal” in the relevant sense to mean “thermal coal” (excluding metallurgical coal) is an important restriction of the scope of the study.

Remember: Diversification is Good

The limited definitions reduce the diversification cost that would be imposed by a stricter divestment policy. Still: those costs are considerable, and ought to concern VPIC “within its role as fiduciary of a U.S. public pension fund,” the PCS report says.

How great would the cost from the reduction in diversification be? That “cannot be estimated,” because there are too many variables, given possible policy shifts, the unknown of which companies will adapt to change successfully and which will not, and the matter of “winning technologies.” One winning technology the report mentions is the shale/fracking revolution of recent years, first in natural gas and then in crude oil, which created such unexpected winners as EOG Resources and Continental Resources.

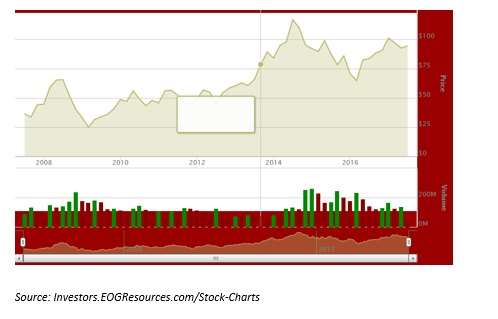

Bernstein doesn’t go into particulars of the shale revolution, but the following illustrates her point: In the summer before the crash of 2008, EOG was selling for between $65 and $66. After the crash, its price fell to just $25.02. But with successful post-crash employment of the new technology, it brought its price up above $110 in the summer of 2014.

EOG Stock Chart, May 2007 to May 2017

There has been some pull back since, which is unsurprising given the crude oil glut that fracking helped create. But clearly any pension fund divesting from EOG before that extraordinary run-up would have imposed upon itself an opportunity cost. Bernstein’s point, which this illustrates, is that the extent of such opportunities lost by a contemplated divestment going forward is quite real, even while it resists precise calculation.

Should VPIC try to divest itself of its private equity holdings in the fossil fuels? The report advises caution about that, as well. First, selling off such holdings in the secondary market would entail “a significant discount to Net Asset Value.” Beyond that there would be costs in monitoring whether the fund managers involved were keeping their hands off the forbidden fuels. Finally, again, there would be opportunity costs.