By Andrew Smith, CAIA

By Andrew Smith, CAIA

The public consensus on Business Development Companies (BDCs) is that they are “the new business bank,” filling the middle-market financing gap left by the financial crisis of 2008 and subsequent banking regulations in the following years. While this is true, it is an oversimplification of the BDC business model.

BDCs are a form of Private Equity Fund; however unlike traditional Private Equity Limited Partnerships (Private Structure Private Equity Funds), they are publicly traded providing investors the liquidity offered from being listed on the public stock exchanges. Further, BDCs have a very specific focus on middle market companies, or companies that are in the $100million to $1billion valuation range, with hyper-growth potential.

BDCs, like private equity funds, only invest in privately offered businesses. Like Private Equity Funds, BDCs invest in a wide range of industries, and their deals carry a variety of structures. Unlike Private Equity funds, which raise capital in the form of Limited Partnership Units from institutional investors, BDCs invest capital that they raise from a wide range of sources, including long-term debt, convertible debt and equity.

BDCs are high-yield investments, in which a majority of their cash-flows are distributed to underlying investors.

As of November 1st 2014, there were 31 publicly listed BDCs with around $25billion in total market capitalization and approximately $40billion in total assets under management when measured by Net Asset Value.

Comparing BDCs to Traditional Companies

The most significant difference between BDCs and traditional companies is that BDCs are limited to financing private companies. BDCs also differ from traditional companies in that they are governed by a management company, and thus are viewed as an investment fund.

BDCs, unlike traditional companies, are taxed as Regulated Investment Companies under the Internal Revenue Code; therefore they pay little or no corporate taxes so long as they meet certain income, diversity and distribution requirements. On average, BDCs distribute 98% of their taxable income to avoid all corporate taxation.

Due to the business model of BDCs, the majority of the revenue and thus the majority of the income generated by BDCs are from investment gains and are taxed as capital gains, providing a tax advantage to investors.

The BDC Business Model

BDCs operate a business model very similar to the merchant banks of “the old days.” BDCs raise capital and then lend or invest this capital in private business. The capital BDCs use to lend or invest in private businesses comes from 3 (sometimes more) main sources.

The first source of capital for BDCs is senior secured debt, also known as corporate bonds. BDCs typically, unlike banking institutions, borrow long term at low fixed rates (200-400 basis points above treasuries); this is the first source of capital. The second source of capital comes from convertible bonds and other hybrid securities. BDCs also raise capital through equity offerings, typically through an Initial Public Offering.

This capital is pooled and used to finance middle-market private businesses. BDCs invest in businesses in a variety of structures, most commonly, through convertible bonds. These convertible bonds pay a coupon, sometimes fixed, sometimes variable, and carry the option to convert the bond to equity as the company grows.

The coupon payments provide income for the BDC to make debt service payments and pay investors the distributions required to maintain their “pass through” taxation structure. As the companies the BDC finances grow in value, the BDC converts the bond to equity and exits the equity through management buyouts, strategic sales, and initial public offerings.

These exits provide significant increases in total assets. Exits also provide cash to pay down debt, cash to pay distributions to investors, and collateral to borrow additional investment capital, which in turn allows the BDC to finance more private companies, larger or more valuable private companies, and provide more financing to each private company.

By providing a private company more capital, BDCs can gain a larger share of the company; they can increase the company budget, which in turn leads to faster growth and a quicker exit. Further, with a larger pool of capital BDCs can broaden their investment diversity leading to less portfolio level risk and a higher propensity towards having a more companies that they’ve invested in turn out to be wild successes and generate very large returns on their investment.

Investor Benefits of BDCs

Investors benefits of BDCs include exposure to private equity, a traditionally difficult to access, highly complex asset class. Private equity is known as a return enhancement asset class, with the top 25% of funds (from a performance perspective) average returns that are 400-800 basis points higher than that of the S&P 500. This performance enhancement is the main reason why institutional investors have consistently increased their target allocations to private equity over the past 3 decades, and are expected to continue to do so.

Investors benefit from BDCs, like with all investments, when the investment generates a return. Traditional private equity funds are not publicly traded and carry no liquidity, therefore they cannot be sold making the sole source of the return to investors in a traditional private equity fund is from investor distributions. BDCs, however, as a publicly traded investment, like any publicly traded stock, generate a return when the stock price increases, and the investor sells the shares of the BDC for more than what they paid. This is known as price appreciation.

When an investor owns stock it is common to receive dividends. As discussed in the “Comparing BDCs to Traditional Companies” section, BDCs distribute, on average, 98% of their taxable income to investors in order to avoid corporate level taxation. BDC dividends are called distributions because of the RIC structure. These distributions are measured in percentage terms, known as the yield. The yield is a ratio of annual distributions relative to the current price of the shares of the BDC.

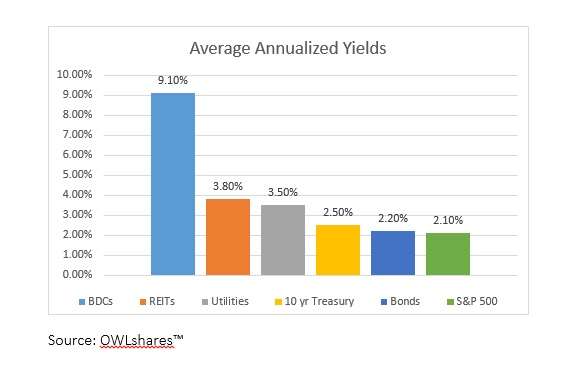

The historical average yield of BDCs over the past 10 years has been 9.1% according to the Wall Street Journal. Translated in dollar terms, this means that if an investor bought $100 worth of BDC shares, on average, the investor would have received $9.10 per year. The yield of BDCs is significantly higher than the yields of other classes of publicly traded investments, such as Utilities & REITs which average approximately 4% Yield, 10-year treasuries, which have averaged about a 3% yield, or the S&P 500, which has averaged approximately 2% yield.

Source: OWLshares™

Yields on BDCs are fairly stable due to their structure as an RIC which must distribute at least 90% of their taxable income, therefore as assets and income grow, which typically leads to stock price growth, the cash distributions must grow as well.

BDC History

The history of BDCs begins in the 1970s when Private Equity funds began gaining significant popularity among large, sophisticated institutional investors. Though Private Equity funds began to increase in popularity there were inherent limitations in the federal laws and regulations that guided the private investment company creation and management. The laws and regulations, as they were blocked Private Equity and Venture Capital fund’s capacity to finance small, growing, and private businesses due to specific language in Section 3(c)(1) of the Investment Company Act of 1940, also known as the 1940 Act, or simple 40 act, which stated that only 100 entities could own an investment company or fund that invested in private businesses. This language explicitly eliminated the potential for funds that provided financing to small or mid-sized private companies from raising capital through a public debt or equity offering.

Private Equity fund managers took action by urging Congress to improve and solve this issue. The legislature listened and acted, passing the Small Business Investment Incentive Act of 1980, which would become known as the 1980 amendments. The goal of the 1980 amendments was to incentivize the creation and management of publicly offered and traded investment vehicles that would finance and invest in private companies. This theoretically would lead to an increase in the flow of capital to small growing businesses, thus stimulating the economy while also providing new investment opportunities to the public. Within the 1980 amendments, Congress created a category of closed-end investment funds that would solely finance and invest in private companies, whether through a debt, hybrid or equity structure. The goal of BDCs would be two-fold, provide financing to growing businesses, thus stimulating the economy, and generate capital appreciation and/or current income, thus increasing the wealth of public investors.

Among other issues, the 1980 amendments sought to achieve these goals by loosening the restrictions that were in place in the 1940 act that discouraged private equity managers from becoming participants in the regulated, public investment management industry. The most notable regulations that were loosened with the 1980 amendments were restrictions in regards to compensation of the manager and the use of borrowing facilities for the private equity funds. With these changes to the law, BDCs were born, however in their infancy; there were only 3 BDCs that were publicly listed at the turn of the century. The following decade would lead to significant growth in the BDC market. From the year 2000 to now, the BDC industry has grown in number of BDCs more than 10-fold. Assets, measured by total BDC market capitalization have increased XX-fold as well. With this growth came opportunity for investors. Investors are now, not only able to gain exposure to private equity, but can do so with significant diversification and liquidity leading to significantly lower portfolio risk when investing in private equity through a basket of BDCs.

Explaining Middle-Market Private Equity Business

Middle market companies, or collectively “the middle market” can be defined by a number of different metrics. Most broadly however, the middle market is defined as companies that carry a valuation in the range of $100million to $1billion. The US middle market is massive; in fact, it is so large, that if it were a country it would rank as the fourth-largest economy in the world. Collectively, the Middle Market makes up 1/3rd of gross annual receipts of US Companies. The middle market is also a significant source of economic growth, employing about 1/3rd of the workforce in the US, with similar numbers across Europe and the developed world.

Middle market companies have significant competitive advantages, in that they are not too large to adapt to changes in the technological landscape often leading to a higher degree of efficiency by deploying newer technologies. This in turn, leads to economic growth by stimulating demand for new technologies and the companies that create them, which, more often than not, are middle market companies themselves.

The middle market is a growth sector among investment opportunities, possibly the largest, not only in size but in potential returns. The majority of middle market companies have the potential to become large-cap brand name industry powerhouses, however often they lack the access to capital to scale their businesses. Middle market companies are too small to go public, have not yet turned a profit, or have not yet reached the value goal the owners have in mind before selling. Further, often these companies, while well known in their industry, do not have the brand power to attract strategic buyers.

Middle market financing is historically underserved by banks, private equity funds, institutional investors and the public. Recently, with new banking regulations, this historically underserved industry has become even more underserved, leading to what has become known as “the Lending Gap”. Financing middle market growth companies, specifically, and industries more broadly, is the metaphorical bread and butter of BDCs. BDCs focus on providing these companies large capital infusions, helping them scale and grow their business, often with the goal of taking the company public through an IPO, selling the company through a strategic acquisition, or negotiating a management buyout. BDCs exit their investment with the goal of generating large total returns, often after only holding for 3-5 years.

While there are many companies that are publicly traded that would be considered middle market, there are many more with significantly larger growth potentials that have not yet taken the company public. For the average investor the only way to access these opportunities is through a BDC. For institutional investors, the most transparent and the only liquid form of investing in these opportunities are also to access them through BDCs.

History of the Middle-Market Private Equity Business

Since the middle ages to the late 1960s and early 1970s, the Middle Market Private Equity business was dominated by banks that either focused on merchant banking, or had a large merchant banking operation. Merchant banking, though not defined by law, is typically defined as a negotiated private equity investment by a financial institution, in which the institution receives unregistered (privately held) securities of either private or publicly held companies.

Merchant banking, at its core, is a focus on making investments in middle-market private companies that have significant growth opportunities, yet do not carry the risk of a start-up or early stage company, as they have already established themselves in their industry. Being established, yet having significant growth opportunities, merchant bankers see an opportunity to make investments that have larger return opportunities than loans, as the equity the merchant bank receives in return for the capital investment is expected to grow significantly over the life of the investment.

With the evolution of banking regulations, merchant banking activities, in the US at least, faded after the great depression, as the 1933 Glass-Steagall Act drew a fine line between investment and commercial banking. As a result, merchant banks evolved into pure investment banks, and commercial banks with merchant banking operations seized to exist. The merchant banking operations were replaced by wealthy individuals and families. As the need for investment in private companies increased, and thus the opportunity to make a profit increased, wealthy individuals and families were replaced by Private Equity funds and firms.

The opportunities available were not, however, the main reason for institutional involvement in Private Equity. In the 1970s changes to the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) rules and regulations, tax laws and changes in security laws led to an increase in demand for private equity investments among the largest institutional investment firms, public and private pension funds. Private and public pension funds found private equity investments appropriate for meeting their long-term objectives. Private equity is viewed by most investors as a return enhancement asset class, with very low liquidity and as pensions do not have a need to have liquid assets, they have continued to increase their allocations to private equity investment opportunities in an attempt to meet or outperform their goals.

While private equity is a fairly broad category, the majority of private equity investments are focused on the middle market. In the case of venture capital most venture capital firms, historically, focused on late stage venture capital, allowing friends, family (of the company founder) and angel investors to accept the risk of a startup or early stage opportunity. The majority of mezzanine private equity financing has been, historically, focused on middle-market (late stage) growth companies, and scaling businesses to their value goals in order for the company to execute their exit strategy. Buyout capital, historically, has focused on middle-market consolidation, spin-off or growth opportunities, taking a controlling stake in the company and either restructuring their capital structure, or the company’s entire operational structure, in order to unleash the value of the company.

This was the case from the 1970s through the late 1990s, however, the bursting of the tech bubble of 1999 led to a shift in paradigm in many ways. Buyout funds became more conservative, focusing on larger companies with severe inefficiencies, and/or distressed companies with a high-propensity to succeed post-bankruptcy. Venture capital firms shifted their focus to early stage companies that have the opportunity for a much shorter time-frame for the investor, typically VC firms now focus on Series A or B capital, and exit in Series C only 3-5 years later.

Mezzanine financing, by private equity firms, has mostly shifted into the private investment in public equity business, providing already public companies with capital needed to achieve certain expansion goals. The middle market has become neglected. The 1980 act (discussed in the “BDC History” section above) allowed for the public offering of private equity funds, but due to a lack of opportunities, very few publicly offered private equity funds had been listed on US exchanges.

As the opportunities in the middle market grew, as did the number of BDCs that became publicly listed. Currently BDCs are the premier middle-market private lender/investor, and have filled, as we will discuss in a later topic, what has become known as “The Lending Gap”.

Dodd-Frank & the New Landscape in Middle–Market Lending

In 2007 the stock market reached its all-time high (at the time), however destruction was right around the corner. Housing prices started to decline, investors, banks and homeowners had massive, highly leveraged, exposure to the housing market, and a fire-sale of both homes, mortgages and mortgage derivatives began to take place. The bursting of the housing bubble led to widespread bank failures, and in September 2008, the stock market collapsed, experiencing its largest decline in decades.

The US government via legislation and subsequent action by the Treasury Department along with the Federal Reserve Bank would take unprecedented measures to try a prevent the US economy from falling into a depression. While the policies and measures taken to do so have been the subject of much debate since, the effects of the deep recession, already in motion, would have lasting effects.

Not only did the economic downturn likely result in a landslide victory for Barack Obama in the presidential elections and landslide victories for the democrat senate and congressional candidates running for office in 2008, but it also led to significant US Government stimulus programs and new regulations. In the financial sector, while stimulus and monetary easing were among major actions, the regulatory changes, namely Dodd-Frank, are likely to have the most long-lasting effect on the banking industry.

While very few, if any, experts are privy on all the new rules and regulations embedded in Dodd-Frank, and while it has yet to be fully implemented, the banking industry has essentially stood still. Lending, particularly lending to businesses that are too large for Small Business Administration (SBA) loans, and too small for public offerings, has dried up significantly, in comparison to the pre-financial crisis activity.

While lending to middle-market companies is likely not prohibited in Dodd-Frank, the uncertainty associated with the rules and regulations within this massive piece of legislation, combined with increases in capital ratios, reserve requirements, and greater clarity on other activities such as SBA lending, mortgage lending, securities lending, and public capital market investing, have resulted in a massive gap in middle-market financing activities by banks.

The Lending Gap – Middle Market Financing Demand Growth

The lending gap is the term used to define the lack of investment capital available to a specific sector of the economy. Since 2008, the lending gap has referred to the lack of investment capital available to lend or invest in middle market private companies. Many professionals believe this lending gap was a direct result of regulatory reforms that occurred after the financial crisis in 2008. The reason for the lack of investment capital, which historically has been provided by private equity firms and banks in tandem, is that private equity firms have shifted their focus to distressed companies and consolidation opportunities, while banks have shifted their operations to focus on large publicly traded businesses and small businesses that are eligible for SBA loans and the subsequent insurance that the SBA provides that bank for making such loans.

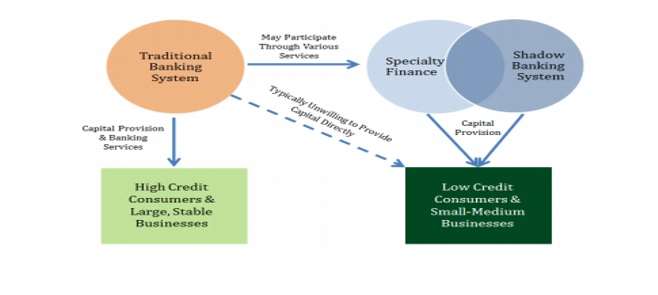

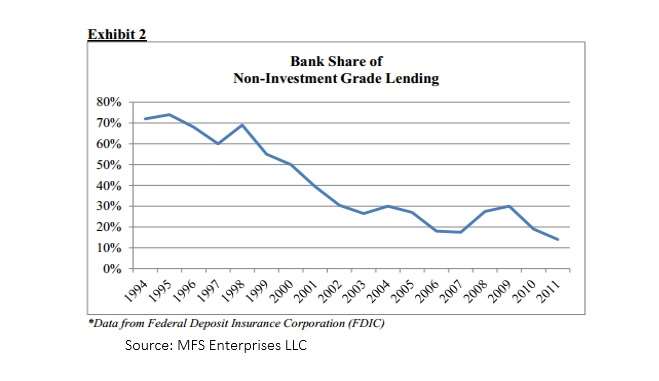

Below is a flow chart that shows where middle market companies find their financing and a chart that shows the decrease in the participation of bank lending to middle market companies.

The lending gap has created a drag on the economy, and even as it begins to close, it will take years for the economic effect of middle market companies finding their financing, to begin to show. Middle market companies are the largest provider of new jobs, as they grow and scale, middle market companies hire hundreds of new employees, build new facilities and corporate campuses, and engage in trade activities with other businesses. This all leads to economic growth as these new jobs provide employees income that they use to consume. Middle market companies however, due to the lending gap, have not been hiring as actively, resulting in slower economic growth in the US.

The 1980s provided legislation, particularly the 1980 act, which would provide a solution to the current lending gap, however, in the post-financial crisis, and post-Dodd-Frank world, it would take time for the provisions in the 1980 act to result in economic activity, and middle-market private equity financing. Since 2008, and more recently, post-Dodd-Frank in 2010, the 1980 act has become much more relevant. The ability to offer publicly traded private equity fund vehicles has become far more economic, with the long line of opportunities to invest in middle market private companies.

How this Effects BDCs

The result, and one of the many unintended consequences of Dodd-Frank has been slower middle-market growth, however it has also presented opportunities. As the lending gap widened, the number of new BDCs being formed has increased, and is beginning to close the gap.

Since the Dodd-Frank passed into law, the formation of new BDCs has increased by well over 100% each year, the total number of BDCs has dramatically increased, the assets managed by BDCs have more than tripled, and the middle-market financing activities of BDCs have been ramped up to meet the demand. BDCs have many opportunities to provide significant financing to middle-market growth companies that have been searching for investment capital for year now. These investments present the opportunity for significant returns on investment and allow BDCs to deploy their investment capital in a diversified manner, lowering their portfolio risk.

While the lending gap, as it was, was an unfortunate and unintended consequence of banking regulations, all in all BDCs have stepped up to fill the gap, and have become a very popular investment vehicle to provide the public exposure to professionally managed investments in middle-market private companies and fill the lending gap. Further, BDCs have opportunities to grow that were created by the lending gap and this unintended consequence of the regulatory reforms post-financial crisis.

The lending gap, thanks to BDCs has mostly been filled, and the supply of middle market investment capital and middle market financing demand has come closer to equilibrium.

Risks of BDCs

While BDCs, being publicly traded, are subject to many of the same risks that any publicly listed stock is subject to, they are also subject to additional risks that may not be relevant to an investment in a traditional company. BDCs employ leverage in their financing activities, meaning that they borrow the majority of what they invest, and attempt to earn a return on their investments that outperforms the interest rate they pay on their loans. Leverage may lead to increased return on investment, but can also lead to increased losses when an investment fails to generate a return.

BDCs are subject to liquidity risk within their portfolio. While the BDCs themselves are publicly traded, and offer liquidity similar to stocks of the same size, the companies BDCs invest in are privately held, and therefore have no liquidity. BDCs rely on executing an exit strategy of either taking the companies they invest in public, or selling the companies they invest in to a strategic buyer. If needed in short order, BDCs would have a difficult time liquidating their investments without taking significant losses; therefore it is extremely important that BDCs are managed by experienced private equity professionals with significant demonstrated success in multiple market cycles.

BDCs are subject to interest rate risks. Any company that borrows at a variable rate has interest rate risk, likewise, any company (traditionally banks) that lends money at variable rates, has interest rate risk. BDCs both borrow and lend. While the majority of BDCs borrowing activities are long term (10 years or longer), and at fixed rates, it is likely that a BDC will refinance their loans when they have large windfalls from investment gains, at which point, interest rates may have risen, leading to a higher cost of capital.

Further, BDCs typically lend at variable rates (with some form of equity convertibility, equity options, or equity warrants), which carries dual sided interest rate risk. If rates go down, which is highly unlikely in today’s environment, but over the long term becomes a more likely scenario, BDCs will receive lower coupon payments (if they haven’t already converted or exited the loan), which will make it more difficult to pay their debt service, or at least make it less profitable.

If interest rates go up, there is the possibility that the companies BDCs lend to become less profitable, grow significantly slower, or in a worst case scenario fail, as a larger portion of their revenue has to go towards debt service payments, leaving less net income to reinvest in growing the business. While the business model of a BDC, borrowing long-term at low fixed rates and lending shorter term at variable rates with equity convertibility, minimizes interest rate risk, investors should still be aware of the risk.

Andrew N. Smith, CAIA is a Co-Founder and Chief Product Strategist for OWLshares and serves as the chairperson of the Steering Committee for the Los Angeles Chapter of the CAIA Association.