Alex Beath, senior research analyst at CEM Benchmarking, the Toronto-based pension research firm, has produced a white paper on the pension fund performance in the U.S. since 1998, and the news he brings is not good (for pension funds themselves, or for the hedge funds to which they have allocated large portions of their portfolios).

The world is awash with talk of a pension crisis and of underfunding. This is so despite the fact that it has been nearly a decade since the global financial crisis and that for most of the period since 2009, equity values have been heading upward. In the period 2009 to 2013, for example, the S&P rose by 75%. One might have expected that to have given pension fund managers, private and public, an opportunity to fund the unfunded liabilities on their books.

Apparently not. Those same years coincided with what was something very close to a zero interest rate policy on the part of the Federal Reserve, and that didn’t help at all. According to a source cited by Beath, unfunded liabilities in public sector DB funds now equal $3.1 trillion, while unfunded liabilities in the private sector’s analogs equals $20 billion.

So: what’s a pension manager to do? Hedge funds pitch themselves in precisely this context. “What you need in your portfolio, friend, is some Absolute Return. That’s our wheelhouse.”

Bad News All Around

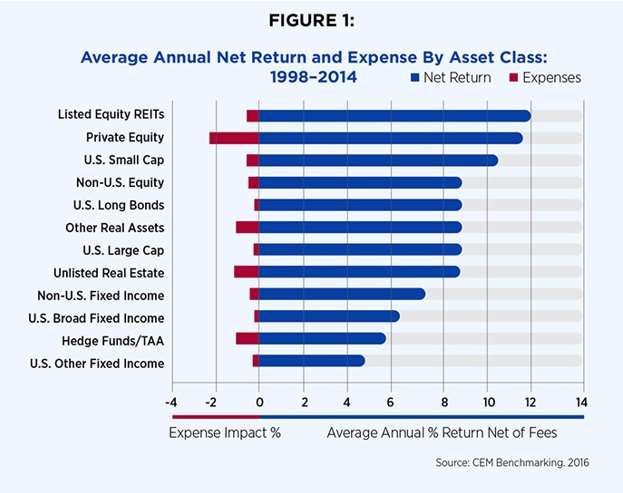

The news in Beath’s study, from the point of view of the alternative investments industry, is that hedge funds performed quite poorly as a component in those portfolios. They were included in CEM’s database with other “tactical asset allocation” strategies, and this asset class showed the second-lowest annual average return of all classes surveyed, beating out only “U.S. Other Fixed Income,” a category that includes the bills kept in the petty-cash drawer.

As the graph below indicates, hedge funds/TAA produced 5.50 percent, which is less than half the average annual return of the Listed Equity REITs, the best performing class.

More bad news? Hedge funds were also considerably more expensive than the REITs, and private equity more expensive than either.

Beath joined CEM in 2010. Before that, he did postdoctoral work in biological physics at the University of California at San Diego. Biophysics is something about halfway in between brain surgery and rocket science.

Private equity is also the most volatile of the asset classes, followed according to this study by non-US equities. The least volatile, unsurprisingly, are the two U.S. fixed-income classifications.

There exists what Beath calls a “complete disconnect” between the way assets have been performing over this 17-year period and the allocation practices of the pension managers, whose confidence in the low scoring hedge fund/TAA category has increased over the period under study. In 1998, these assets drew an allocation of only 1.46% from pension funds. In 2014, that number was 8.36%, nearly six times that size.

A Missed Opportunity

The allocation to Listed Equity REITS also increased over this period, but the increase was from a very low point to a still very low point, from 0.36% to 0.62%.

According to Beath, the fact that this class was top performing but continues to be the lowest allocation in the study represents “a significant missed opportunity for pension funds and may point to a strategy for improving future returns.” If the US managers of private defined benefit plans had allocated into REITS what they in fact allocated to hedge funds, and vice versa, then they would have generated an additional $64 billion in assets over the period under study. That’s a stunning figure. It is more than three-times the above mentioned unfunded-liability figure for such funds.

An incidental point about the database: some large corporate sector funds outperformed just because they ‘lucked out’ in a nonrepeatable sort of way. Specifically, they shifted to liability-driven investing just before the global crisis, increasing their allocation to U.S. long duration bonds as a consequence. But for that one-off, the aggregates would look worse than they do.

Beath had assistance in this work from Chris Flynn, CFA.