The structure of financial markets has changed substantially since the 2014 publication of Michael Lewis’ Flash Boys. Much that was shocking and new then is now taken for granted. Also, the world of investments is in a sense more democratic now, with Robinhood transforming the model of retail investing, and those retail investors becoming an important part of the Big Picture.

Yet we still don’t understand the new world we inhabit. At least one of Lewis’ original points still holds: it is important for this world to be transparent to itself, and currently it is remarkably opaque.

With just that point in mind, in November 2018 the Securities and Exchange Commission adopted amendments to rule 606 of Regulation NMS to require broker-dealers to report on their order handling and routing services.

Transparency about Liquidity

In late May the first reports from the operation of SEC rule 606 went live, offering first quarter 2020 trading data. The format for 606 reporting includes the net liquidity rebates paid by the exchanges and the order routing revenue paid by market makers.

Alphacution Research Conservancy has posted a paper drawing on this new data to take what it calls some “baby steps” toward an understanding of the new economics of liquidity.

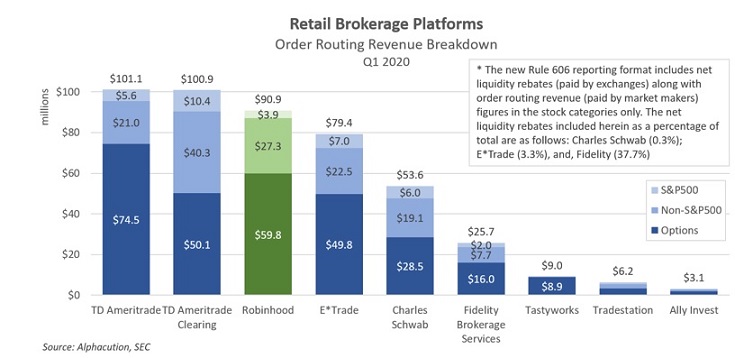

One surprise: Tastyworks. What the reports indicate is that $487.7 million of order routing revenue goes to a group of at least 10 public and private entities, retail-oriented brokerages. One of these is Tastyworks, which Paul Rowady, director of research for Alphacution, and author of the report says he had “never heard of before.”

The odd name, “Tastyworks,” seems to be the outgrowth of a pun on the metaphorical use of “dough.” Kristi Ross founded dough Inc in 2014. This was a front-end trading technology platform, which was in due course rebranded to Tastytrade on the one hand (a financial media company) and Tastyworks on the other. Tastyworks makes a good chunk of its dough routing orders for options ($8.9 million), and $100k on equities, rounding its revenue from these courses out to $9 million.

But let’s look again at the whole pie, the $487.7 million mentioned above. Of that, roughly 6%, or $29.6 million, comes from the exchanges as net liquidity payments.

The rest, $358.1 million, a pretty tasty amount, which is paid by 11 entities, including some very familiar names, Citadel Securities and Susquehanna International Group. Citadel represents $172.2 million of the total payments.

Turning to the Order-Flow Payees

Tastywork’s $9 million makes it only the 7th largest in this group. Here is the chart, from the SEC by way of Alphacution.

Another surprise? Robinhood (appropriately presented above in forest green) attracts much more of the order routing revenue that Rowady had expected: $90.9 million. He suspects this is in part due to Silicon Valley’s habit of over-valuation.

Rowady also turns to the issue of rates. The data indicate a great variation in how much is paid for order routing across order types. Especially in the case of Robinhood the retail broker receives more for the most common and most liquid securities relative to the less common and less liquid securities. Robinhood receives $1.60 for a hundred shares of an S&P 500 market order. For a hundred options, it will receive less than $0.50. For non-S&P 500 equities, less than $0.40.

Rowady asks, “could this represent a tip of the hand as to the underlying strategy?” Well, “yes, of course,” one wants to inject. It has become the common coin of #FinTwit, expressed sometimes with rage and sometimes with resignation, that Robinhood makes money by selling the order flow of customers who naively believe they are getting something for free.

There is an old saying: “if you’re not paying for it, you’re not the customer, you’re the product.” That is certainly the case here. And though it sounds nefarious, Robinhood’s success shows that there are numbers of retail investors who accept “being the product.” The company is not secretive about its business model, and it is too heroic an assumption to say that acceptance of this deal is in every case naivete. It is a choice.

And the Conclusion is…

That business model does help explain why order flow for the “mainstream” investments receive the highest rates. Its value as data is greater for those investments.

Many of the Alphacution report’s conclusions are in the spirit of the final words of a manuscript that the great philosopher William James left behind when he died. “What has concluded that we should draw conclusions?” In particular, the report observes that the rule 606 data does not match up well with the Form 10-Q data, which indicates that “we have not yet fully accounted for the sources and methods of order flow economics.”

Understanding the new world created in recent years, by HFT, by machine learning, by democratization, and yes by liquidity arrangements that lend themselves to snark, is going to be a big task.