By Aaron Filbeck, CFA, CAIA, CIPM, FDP, Director, Global Content Development at CAIA Association

One of my favorite sci-fi movies of all time is Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar. While there so many great elements to the film, including a killer score, one of the most interesting tensions that emerges from the plot is the intersection of science, the individual human experience, and decision making when all models fail.

Romilly: ”That's relativity, folks.”

For many retirees, like the crew aboard The Endurance, we’ve entered uncharted territory. Negative interest rates have probably only just begun to be incorporated in academic textbooks, risk premiums are distorted (and may be broken), and valuations seem not to matter anymore. Oh, and Dogecoin is a thing. Compounding this issue is that we continue to be on our own to fend for our own retirement outcomes as the pension market shrinks. Gone are the days when you could rely on a steady paycheck from your pension, without taking any investment risk yourself.

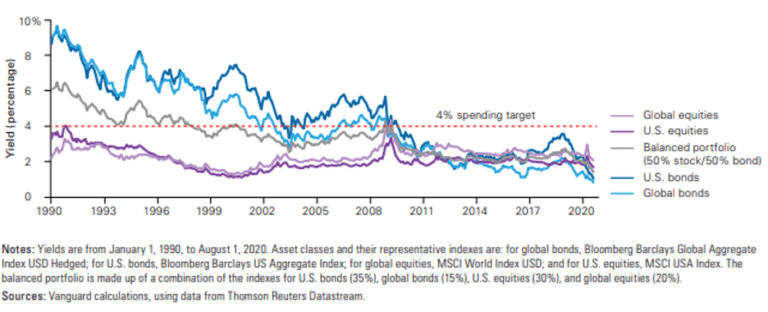

It’s a rule of thumb that a retiree should only withdraw between 4-6% of their total portfolio per year in retirement to avoid dipping into their portfolio principal and/or run out of money. In the early 1990s through the mid-2000s, that was pretty easy—you could put 100% of your portfolio in high quality (i.e. government) bonds and generate that much and then some.

Current yields of traditional asset classes

Source: Vanguard

Today, that’s no longer the case, as shown in the chart above. Vanguard recently released a paper that acknowledges a necessary shift towards total return investing over optimizing a yield-maximized portfolio. Frankly, it’s because there’s not much to optimize on the income front. Traditional fixed income yields are mostly sub-2% (if that!), far below the lower bound of that rule, and even a 60/40 portfolio of U.S. stocks and bonds only yields 3.21% with far more volatility.[1] That last part is important and will be discussed in the coming sections.

What is “Risk” for a Retiree?

Professor Brand: I’m not afraid of death. I’m an old physicist. I’m afraid of time.

Individuals define risk differently than institutions, with the most prominent definition of risk being loss of capital rather than statistical measures, such as standard deviation.[2] I would add to this idea, in that time, which is an asset to an “asset accumulator”, becomes a liability to an “asset decumulator.” More importantly, individual investors are subject to sequence of returns risk, or the risk of an unfavorable sequence of returns. This risk increases as an individual approaches, and eventually enters retirement, and gradually decreases as the individual nears death. Even if an individual client experiences attractive long-term returns, the path to obtain those returns could be detrimental to a client’s financial situation. And one of the largest variables, aside from the dollar amount of withdraws, is time. “Can I make this money last?”

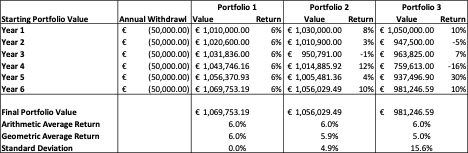

Illustration of sequence of returns risk

Source: Author’s calculations

The chart above illustrates three hypothetical portfolios that generate the exact same arithmetic return of 6% per year. However, all three portfolios generate this return stream in different ways. Portfolio 1 earns a 6% arithmetic return by generating the same return every year (a standard deviation of 0%), while Portfolios 2 and 3 generate this return with differing, and more volatile, return streams. In this hypothetical scenario, all three portfolios start with EUR 1,000,000 and require EUR 50,000 withdrawn from the portfolio every year to fund the individual’s lifestyle. Notice, the more volatile the return stream, the lower the geometric return, and the lower the final portfolio value at the end of the period. That’s compounding, folks!

Reaching for Yield, Hiding from Volatility

Cooper: Murphy’s Law doesn’t mean that something bad will happen. It means that whatever can happen, will happen.”

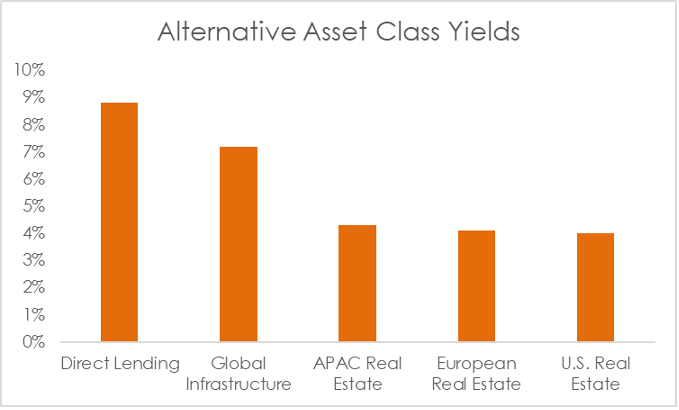

With this backdrop, it might be tempting to look to alternative sources of income, with lower levels of liquidity, to help bridge the gap.

The table below shows the alternative asset class yields available to investors in private capital. Most of these yields either hit or exceed the minimum rule-of-thumb distribution rate (4%) an individual investor would use when trying to pull living expenses from their portfolio. It’s no wonder there’s an increased appetite for these assets.

Source: JPMorgan’s Q1 Guide to the Markets, CAIA Association

With yields that could be considered competitive with global equity returns, it’s also probably no surprise to see that private credit (direct lending) funds have seen assets under management increase twenty-fold in the course of two decades, with interest in infrastructure right behind it. Low yields and higher regulatory hurdles in the public markets have certainly driven a lot of this activity. Not only that, but the stated volatility on many of these products are far below their public counterparts. Best of both worlds, pun intended. But, just like in public markets, private market investors should be cautious when chasing yield. Not only does the incorporation of these asset classes introduce additional risk drivers to the portfolio (e.g., more credit risk relative to a traditional core bond portfolio), but it also introduces illiquidity, which structurally and meaningfully alters the time horizon of the investor’s portfolio and reduces the transparency enjoyed by investors in traditional markets. While it may improve the portfolio’s statistical optics, it may not necessarily mitigate the ultimate economic risk for a retiree—permanent loss of capital, or poor portfolio outcomes that increases longevity risk.

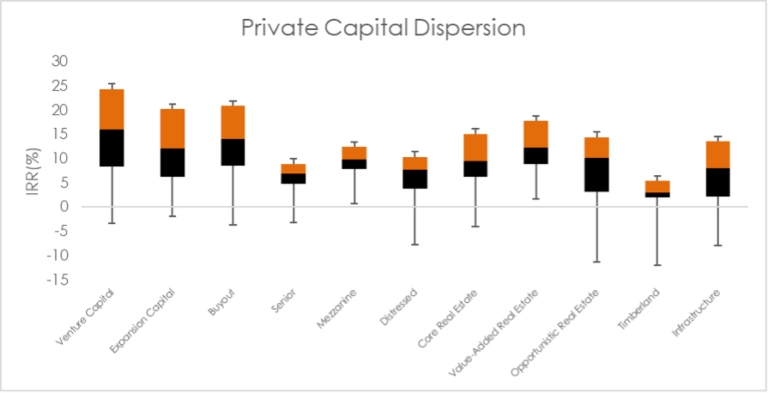

Dispersion of private capital returns

Source: Burgiss, CAIA Association Note: Time period is from September 30, 2010 through September 30, 2020

The chart above shows the dispersion of returns (IRRs, a return metric which is flawed but should be used here for my illustrative point) for multiple private capital strategies, which just shows how important investing with the right manager is for an investor. In the example of private credit, the starting yield may be attractive, but defaults and markdowns could end up destroying value for the total portfolio, as opposed to simply underperforming and index or client expectations. After all, at some point, these private funds return capital to shareholders, so the value will be realized eventually…or not.

Tools for a New World

CASE: It's not possible. Cooper: No. It's necessary.

Professionals who work with individual clients face unprecedented and structural challenges today relative to those of the past. Not only have the withdraw demands not changed, but they cannot be provided through passive income. Total return investing requires more decisions – what do you sell? How do you manage cash flows that do come into the portfolio? These problems won’t be solved in an article like this, but I can provide some things to think about as we venture into this new normal:

- Identify the role of Illiquidity – illiquidity might be your friend in the accumulation phase, but it can be difficult in the decumulation phase. That said, the appropriate allocation to illiquid assets is somewhere between 0 and 100% (helpful right?). It’s helpful to think about illiquidity just like any other risk metric, such as beta or standard deviation, and be thoughtful about cash flow timing and vintage year diversification.

- Rebalance…smartly – Since income-only strategies are not likely to be the strategy of the future, investors must mitigate sequence of return risk by rebalancing more actively. Of course, having a process and framework is important, but so is paying attention to what the market is giving you and where the cash flows are coming from. It’s less about timing the market, but instead focusing on the objective you are trying to accomplish for a retiree. Also, I should note that “actively” doesn’t mean frequently – sometimes the best thing to do is to do nothing!

- Understand Your Limitations – especially in private markets, where manager dispersion is highest, it’s important to know yourself as an allocator of capital. Manager selection isn’t just identifying a good manager, it’s about identifying your ability to identify a good manager. Alternatives encompass multiple strategies and asset classes; identifying which ones will be the largest value-add for your portfolio, allocating to them, and avoiding the rest isn’t a bad strategy. Jumping blindly into alternative investments, and thinking of them as the saving grace from your portfolio, is…and it’s a recipe for poorer outcomes.

While we can use history as a guide, we can’t base all of our decisions on historical events – the assumptions have changed. But we can develop loose frameworks to help guide those decisions, while simultaneously acknowledging that it doesn’t always work on autopilot.

Seek education, diversification of both your portfolio and people, and know your risk tolerance. Investing is for the long term.

Aaron Filbeck, CFA, CAIA, CIPM, FDP is Director of Global Content Development at CAIA Association. You can follow him on LinkedIn and Twitter.

[1] JPMorgan Q1 Guide to the Markets

[2] Jennings, Horan, Reichenstein and Brunel (2011)